An effort was being made by a senior officer to explain away the ''pushbacks'' of Rohingya boatpeople to their deaths as somehow being in the national interest of Thailand.

''Are you a Thai?''

Not a lot has changed in five years.

We know that there are still senior Royal Thai Navy officers who continue to ask journalists: ''Are you a Thai?'' as if that somehow justifies the mistreatment of innocent men, women and children, the human trafficking, the loss of lives.

The right answer to the question, ''Are you a Thai?'' is, ''Of course I am a Thai, but the treatment of Rohingya boatpeople requires everyone to answer as a human being first.''

Thailand's coup commander, General Prayuth Chan-ocha, was speaking on television tonight almost at the same time as the US State Department's Trafficking in Persons report was being unveiled in Washington.

We suspect that if the general was asked in the context of human trafficking: ''Are you a Thai?'' he would answer: ''Of course I am a Thai, but first I am a human being.''

He appears to not be the kind of military officer who would use the issue of national security as an excuse for deception and the abuse by the military and authorities of the downtrodden.

And if the media asks him in the next few days about what will follow in terms of Thailand's downgrading on the US State Department's Trafficking in Persons report, we hope he will respond in similar fashion to his televised speech tonight.

He aims to eliminate the exploiters and to make all systems transparent to the people of Thailand, and to the world. At Phuketwan, we find that a welcome change of approach.

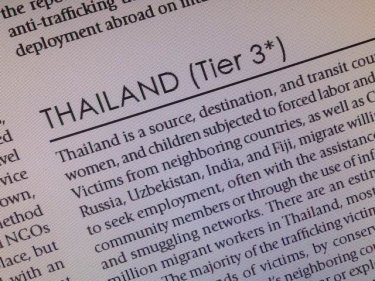

Here is the Thailand section of the Trafficking in Persons report in full:

Thailand is a source, destination, and transit country for men, women, and children subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking. Victims from neighboring countries, as well as China, Vietnam, Russia, Uzbekistan, India, and Fiji, migrate willingly to Thailand to seek employment, often with the assistance of relatives and community members or through the use of informal recruitment and smuggling networks.

There are an estimated two to three million migrant workers in Thailand, most of whom are from Burma. The majority of the trafficking victims within Thailand tens of thousands of victims, by conservative estimates are migrants from Thailand's neighboring countries who are forced, coerced, or defrauded into labor or exploited in the sex trade.

A significant portion of labor trafficking victims within Thailand are exploited in commercial fishing, fishing-related industries, low-end garment production, factories, and domestic work; some victims are forced to beg on the streets.

There are reports of corrupt officials on both sides of the border who facilitate the smuggling of undocumented migrants between Thailand and neighboring countries including Laos, Burma, and Cambodia; many of these migrants subsequently become trafficking victims.

Unidentified trafficking victims are among the large numbers of undocumented migrants deported to Laos, Burma, and Cambodia each year. Burmese, Cambodian, and Thai men are subjected to forced labor on Thai fishing boats that travel throughout Southeast Asia and beyond; some men remain at sea for up to several years, are paid very little, are expected to work 18 to 20 hours per day for seven days a week, or are threatened and physically beaten.

A 2013 report found that approximately 17 percent of surveyed fishermen, who primarily worked on short haul vessels spending less than one month at sea, experienced forced labor conditions, often due to threats of financial penalty including not being fully remunerated for work already performed.

A 2010 assessment of the cumulative risk of labor trafficking among Burmese migrant workers in the seafood industry in Samut Sakhon found that 57 percent of the 430 workers surveyed experienced conditions of forced labor. As fishing is an unregulated industry region-wide, fishermen typically do not have written employment contracts with their employers.

Reports during the year indicate this form of forced labor continues to be prevalent, and that increasing international scrutiny has led traffickers to use new methods, making their crimes more difficult to detect. Men from Thailand, Burma, and Cambodia are forced to work on Thai-flagged fishing boats in Thai and international waters and were rescued from countries including Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Timor-Leste. The number of Cambodian victims rescued from Thai fishing vessels in countries around the world more than doubled in 2013. Cambodian and Burmese workers are increasingly unwilling to work in the Thai fishing industry due to dangerous and exploitative work conditions which make them more vulnerable to trafficking.

There continued to be reports that corrupt Thai civilian and

military officials profited from the smuggling of Rohingya asylum

seekers from Burma and Bangladesh (who transit through

Thailand in order to reach Malaysia or Indonesia) and were

complicit in their sale into forced labor on fishing vessels.

Thai navy and marine officials allegedly diverted to Thailand

boats carrying Rohingya asylum seekers en route to Malaysia

and facilitated the transfer of some migrants to smugglers and

brokers who sold some Rohingya into forced labor on fishing

vessels.

Additionally, there are media reports that some Thai police officials systematically removed Rohingya men from

detention facilities in Thailand and sold them to smugglers and

brokers; these smugglers and brokers allegedly transported the

men to southern Thailand where some were forced to work as

cooks and guards in camps, or were sold into forced labor on

farms or in shipping companies.

Traffickers (including labor brokers) who bring foreign victims into Thailand generally work as individuals or in unorganised groups, while those who exploit Thai victims abroad tend to be more organised. Labor brokers, largely unregulated and of both Thai and foreign nationalities, serve as intermediaries between job-seekers and employers; some facilitate or engage in human trafficking and collaborate with employers and at times with corrupt law enforcement officials.

Foreign migrants, members of ethnic minorities, and stateless

persons in Thailand are at the greatest risk of being trafficked,

and they experience various abuses that may indicate trafficking,

including the withholding of travel documents, migrant

registration cards, work permits, and wages. They may also

experience illegal salary deductions by employers, physical

and verbal abuse, and threats of deportation.

Undocumented migrants are highly vulnerable to trafficking due to their lack of legal status, which often makes them fearful of reporting problems to government officials. Many migrant workers incur exorbitant debts, both in Thailand and in countries of origin,

to obtain employment and may therefore be subjected to debt

bondage.

Members of ethnic minorities and stateless persons

in Thailand face elevated risks of becoming trafficking victims.

Highland men, women, and children in the northern areas of

Thailand are particularly vulnerable to trafficking; UN research

cites a lack of legal status as the primary causal factor of their

exploitation. Some children from Thailand, Cambodia, and

Burma are forced by their parents or brokers to sell flowers,

beg, or work in domestic service in urban areas.

Thai victims are recruited for employment opportunities abroad and deceived into incurring large debts to pay broker and recruitment fees, sometimes using family-owned land as collateral, making them vulnerable to exploitation at their destination. Thai nationals have been subjected to forced labor or sex trafficking in Australia, South Africa, and in countries in the Middle East, North America, Europe, and Asia. Some Thai men who migrate for low-skilled contract work and agricultural labor are subjected to conditions of forced labor and debt bondage.

The majority of Thai victims identified during the year were

found in sex trafficking. Women and girls from Thailand, Laos,

Vietnam, and Burma, including some who initially intentionally

seek work in Thailand's extensive sex trade, are subjected to sex

trafficking.

Child sex trafficking, once known to occur in highly

visible establishments, has become increasingly clandestine,

occurring in massage parlors, bars, karaoke lounges, hotels, and

private residences. Children who have false identity documents

are exploited in the sex trade in karaoke or massage parlors.

Local NGOs report an increasing use of social media to recruit

women and children into sex trafficking. Victims are subjected

to sex trafficking in venues that cater to local demand and in

business establishments in Bangkok and Chiang Mai that cater

to foreign tourists' demand for commercial sex.

Thailand is a transit country for victims from North Korea, China, Vietnam, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Burma subjected to sex trafficking or forced labor in countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Russia, South Korea, the United States, and countries in Western Europe.

There were reports that separatist groups in southern

Thailand continued to recruit and use children to commit acts

of arson or serve as scouts.

The Government of Thailand does not fully comply with the

minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking. In the

2012 and 2013 TIP Reports, Thailand was granted consecutive

waivers from an otherwise required downgrade to Tier 3 on

the basis of a written plan to bring itself into compliance with

the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking.

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) authorises a maximum of two consecutive waivers. A waiver is no longer available to Thailand, which is therefore deemed not to be making significant efforts to comply with the minimum standards and is placed on Tier 3.

The Government of Thailand improved its anti-trafficking

data collection. It reported convicting 225 traffickers under

the 2008 anti-trafficking law and related statutes in 2013.

Overall anti-trafficking law enforcement efforts remained

insufficient compared with the size of the problem in Thailand,

and corruption at all levels hampered the success of these

efforts.

Despite frequent media and NGO reports documenting

instances of forced labor and debt bondage among foreign

migrants in Thailand's commercial sectors - including the

fishing industry - the government demonstrated few efforts

to address these trafficking crimes.

It systematically failed to investigate, prosecute, and convict ship owners and captains for extracting forced labor from migrant workers, or officials who may be complicit in these crimes; the government convicted two brokers for facilitating forced labor on fishing vessels. The government did not make sufficient efforts to proactively identify trafficking victims among foreign migrants, who remained at risk of punishment for immigration violations.

A critical shortage of available interpretation services across government agencies limited efforts to identify and protect foreign victims, and authorities identified fewer foreign labor trafficking victims than it did during the previous year. There were media reports in 2013 of trafficking-related complicity by Thai civilian and navy personnel in crimes involving the exploitation of Rohingya asylum seekers from Burma and Bangladesh. The Thai navy claimed that these reports were false and responded by filing criminal defamation charges against two journalists in Thailand for re-printing these reports.

Impunity for pervasive traffickingrelated corruption continued to impede progress in combating trafficking.

Recommendations for Thailand:

Promptly and thoroughly investigate all reports of government

complicity in trafficking, and increase efforts, particularly through

the Department of Special Investigation and the Office of

National Anti-Corruption Commission and the Office of Public

Sector Anti-Corruption Commission, to prosecute and punish

officials engaged in trafficking-related corruption; increase efforts

to prosecute and convict trafficking offenders, including those

who subject victims to forced labor in Thailand's commercial

and export oriented sectors; develop and implement victim

identification procedures that prioritise the rights and safety

of potential victims; significantly increase efforts to proactively

identify victims of trafficking among vulnerable populations,

particularly foreign migrants, deportees, and refugees; pursue

criminal investigations of cases in which labor inspections

reveal indicators of forced labor - including the imposition of

significant debts by employers or labor brokers, withholding

of wages, or document confiscation; cease prosecuting criminal

defamation cases against researchers or journalists who report on

human trafficking; recognizing the valuable role of NGOs and

workers' organisations in uncovering the nature and scope of

human trafficking in Thailand, work to establish an environment

conducive to robust civil society participation in all facets of

understanding and combating human trafficking; allow every

adult trafficking victim - including sex trafficking victims - to

travel, work, and reside outside shelters in accordance with

provisions in Thailand's anti-trafficking law; significantly increase

the availability of interpretation services across government

agencies with responsibilities for protecting foreign migrants;

increase incentives for victims to cooperate with law enforcement

in the investigation and prosecution of trafficking cases; consider

establishing a dedicated court division, or take other measures to

consistently expedite the prosecution of trafficking cases; develop

and provide specialized services for child sex trafficking victims

and take appropriate steps to ensure their cases progress quickly; implement court procedures which prioritize the protection of witnesses; restrict bail to alleged trafficking offenders to prevent flight; enact legislation that protects officials against legal retaliation for pursuing trafficking cases; consistently include trained social workers or victim service organizations in victim screening interviews in safe and private spaces; process and approve legal status applications at the national, district, and

provincial level in a timely manner; provide legal alternatives to

the removal of foreign trafficking victims to countries in which

they would face retribution or hardship; increase efforts to seize

assets of trafficking offenders and ensure these funds directly

benefit victims; increase anti-trafficking awareness efforts directed at employers and clients of the sex trade, including sex tourists; and make efforts to decrease the demand for exploitive labor.

Prosecution

The Thai government improved its anti-trafficking data

collection, allowing more accurate reporting on prosecutions

and convictions. Thailand's 2008 anti- trafficking law

criminally prohibits all forms of trafficking and prescribes

penalties ranging from four to 10 years imprisonment

penalties that are sufficiently stringent and commensurate

with penalties prescribed for other serious offenses, such as

rape. The government reported investigating 674 trafficking

cases in 2013, an increase from 306 cases in 2012. Only 80

investigations involved suspected cases of forced labor of migrant

workers, despite the reported high prevalence of this form of

trafficking in Thailand. The government reported prosecuting

483 suspected traffickers, including 374 for sex trafficking, 56

for forced begging, and 53 for other forms of forced labor. The

government reported convicting 225 traffickers using the antitrafficking law and various other statutes in 2013. The majority

of convicted offenders received sentences ranging from one to

seven years' imprisonment, with 29 receiving prison sentences

greater than seven years and 31 receiving sentences of less than

one year. The Anti-Money Laundering Office seized assets of two

convicted traffickers valued to the equivalent of approximately

$1.1 million.

The government did not hold ship owners, captains, or complicit

government officials criminally accountable for labor trafficking

in the commercial fishing industry. With investigative support

from NGOs, the government prosecuted and convicted two

Burmese brokers for facilitating the forced labor of Burmese

men in the commercial fishing industry; one was sentenced

to 33 years' imprisonment and one was sentenced to three

years and six months' imprisonment. A Thai accomplice, a

pier manager who held at least 14 victims in confinement,

was not prosecuted for his role in their victimisation, but was

convicted and sentenced to three months' imprisonment for

providing shelter to undocumented workers. The government

reported no investigations, prosecutions, or convictions of public

officials or private individuals for allegedly subjecting Rohingya

asylum seekers to forced labor in Thailand's commercial fishing

sector. There were no developments in the Supreme Court's

consideration of an appeal of a 2009 conviction, upheld in 2011,

of two offenders found guilty of subjecting 73 victims to forced

labor in a shrimp-peeling factory; both offenders remained

free on bail during the reporting period for a second year. The

government addressed cases involving illegal recruitment fees

and withholding of wages as civil violations under the Labor

Protection Act instead of as criminal cases under the 2008

anti-trafficking law.

In one case, the government reported investigating and

disciplining 33 local police officers on suspicion of protecting a

brothel where child sex trafficking victims were found. However,

trafficking-related corruption remained widespread among

Thai law enforcement personnel. Credible reports indicated

some corrupt officials protected brothels, other commercial

sex venues, and food processing facilities from raids and

inspections; colluded with traffickers; used information from victim interviews to weaken cases; and engaged in commercial

sex acts with child trafficking victims. Local and national-level

police officers established protective relationships with traffickers

in trafficking hot-spot regions to which they were assigned. Thai

police officers and immigration officials reportedly extorted

money or sex from Burmese migrants detained in Thailand for

immigration violations and sold Burmese migrants unable to

pay labor brokers and sex traffickers. Although the government

reported conducting an internal investigation of trafficking related

military complicity in the exploitation of Rohingya

asylum seekers, observers claimed that the government failed

to thoroughly investigate the allegations. In December 2013,

the Thai navy filed a defamation lawsuit against two journalists

from a local newspaper that published excerpts of media reports

that alleged trafficking-related complicity by Thai civilian and

navy personnel.

The government continued to provide training to thousands

of public officials on trafficking victim identification and the

provisions of the anti-trafficking law. It reported numerous

cooperative international investigations. In one case, it

responded to information provided by Burmese police, leading

to the rescue of 10 Burmese victims forced to work in a food processing factory in Thailand, and the arrest of seven suspected

traffickers. In a separate case, responding to a request from a

civil society organisation, officials cooperated with foreign

counterparts in South Africa to rescue Thai women subjected to

sex trafficking and arrested three alleged perpetrators. Challenges

with collaboration between police and prosecutors limited the

success of prosecution efforts. Interagency coordination was

weakened by a rudimentary data collection system that made

it difficult to share information across agencies. Local observers

reported officials were vulnerable to retaliation suits or charges of

defamation if cases were unsuccessful - a disincentive to pursue

difficult cases. Overall, the justice system increased the speed at

which it resolved criminal cases, though some trafficking cases

continued to take three years or longer to reach completion.

Frequent personnel changes hampered the government's ability

to make progress on anti-trafficking law enforcement efforts,

and some suspected offenders fled the country or intimidated

victims after judges decided to grant bail, further contributing

to a sense of impunity among traffickers.

Protection

The government's efforts to identify and protect trafficking

victims remained inadequate. The government provided

services to 744 trafficking victims, and the Ministry of Social

Development and Human Security (MSDHS) reported that

it provided assistance to 681 victims at government shelters

(an increase from 526 in 2012), including 305 Thai victims

(compared with 166 Thai victims in 2012), 373 foreign victims

(compared with 360 foreign victims in 2012), and three whose

nationalities were unknown. Authorities identified an additional

63 Thai victims subjected to sex or labor trafficking overseas;

these victims were processed at a government center upon

arrival in the Bangkok airport and returned to their home

communities. The government identified 219 foreign labor

trafficking victims in 2013 - a decrease from 254 identified in

2012. The Thai government continued to refer victims to one

of nine regional trafficking shelters run by the MSDHS, where

they reportedly received counseling, limited legal assistance,

and medical care. Some interpretation services were available

in Burmese, Cambodian, Chinese, and certain ethnic minority

languages. Thai embassy officials, in collaboration with MSDHS,

rescued and repatriated Thai victims identified in Malaysia

and South Africa. There were reports that some personnel in a

Thai embassy overseas may have been unwilling to respond to

requests to assist Thai victims in that country.

The government responded to information provided by NGOs

and foreign governments to identify and rescue victims. Although

it reported using systematic procedures to screen for victims

among vulnerable populations and placed posters explaining

victims' rights in deportation facilities to encourage victims to

self-identify, its proactive efforts to screen for victims among

vulnerable groups remained inadequate. NGOs reported that the

government did not provide adequate interpretation services or

private spaces to screen potential victims, severely limiting the

effectiveness of such efforts. During the year, the government

trained 95 new interpreters. The government reported deploying

multi-disciplinary teams to interview 2,985 Rohingya asylum

seekers and Bangladeshi migrants identified during raids

on camps in southern Thailand to screen for indications of

trafficking. Despite media and NGO reports throughout the year

that some individuals among this population were subjected

to forced labor in Thailand, the government did not identify a

Rohingya victim of trafficking. Experts highlight that Rohingya

victims may have been hesitant to identify themselves as

trafficking victims due to fears they would subsequently be sent

back to their country of origin. Thailand's laws do not provide

legal alternatives to removal for foreign trafficking victims who

may face retribution or hardship in their countries of origin.

Many victims, particularly undocumented migrants who feared

legal consequences from interacting with authorities, were

hesitant to identify themselves as victims, and front-line officials

were not adequately trained to identify indicators of trafficking

when victims did not self-identify. Law enforcement officers

often believed physical detention or confinement was the

essential element to confirm trafficking and failed to recognise

exploitive debt or manipulation of undocumented migrants'

fear of deportation as non-physical forms of coercion used in

human trafficking. In some provinces, the government used

multidisciplinary teams consisting of social workers and law

enforcement officers to identify and rescue victims, but only law

enforcement officials were able to make the final determination

to certify an individual as a trafficking victim; in cases of debt

bondage, the denial of certification at times occurred over the

objection of social service providers.

The government issued six-month work permits and visas

(renewable for the duration of court cases) that allowed 128

foreign victims to work temporarily in Thailand during the course

of legal proceedings, an increase from 107 in 2012. Seventeen

adult female victims received permits; some victims were not

allowed to work due to the government's assessment that it

would be unsafe or unhealthy for them to do so. Women without

work permits were typically required to stay in government

shelters and could not leave the premises unattended until Thai

authorities were ready to repatriate them. There were reports that

victims, including those allowed to work, were only given a copy

of their identity documents and work permits, while the original

documents were kept by government officials. The government

disbursed the equivalent of approximately $145,000 from its

anti-trafficking fund to victims. These funds were allocated

among 525 victims, including paying for the repatriation of 335

foreign victims. Seventy-five trafficking victims benefited from

the government's general crime victim compensation scheme,

which disbursed the equivalent of approximately $65,000 in

2013. The 2008 anti-trafficking law includes provisions for

civil compensation for victims; the government filed petitions

on behalf of 68 victims, and requested a total equivalent of

approximately $580,000, though there were no judgments

allowing the disbursement of these funds during the year.

Although more than three-quarters of identified victims were

children, the government did not offer specialized services for

child sex trafficking victims. The prosecution of some cases

involving foreign child victims continued to take two years or

longer. Judicial officials did not always follow procedures to

ensure the safety of witnesses; victims, including children, were

at times forced to testify in front of alleged perpetrators and

some were forced to publicly disclose personal information, such

as their address, which put them at serious risk of retaliation.

The government did not provide legal alternatives to victims

who faced retribution or hardship upon return to their home

countries; foreign victims were systematically repatriated if

they were unwilling to testify or following the conclusion of

legal proceedings. NGOs reported concerns over the lack of

appropriate options for foreign children whose families were

complicit in their trafficking or who could not be identified. Local

observers in Cambodia reported that a number of Cambodians,

who were identified as trafficking victims or people vulnerable

to trafficking by Thai authorities, were nonetheless held in Thai

detention centers for one month prior to their repatriation. A

2005 cabinet resolution established that stateless trafficking

victims in Thailand could be given residency status on a case by-

case basis; however, the Thai government had yet to report

granting residency status to a foreign or stateless trafficking

victim. Thai law protects victims from being prosecuted for acts

committed as a result of being trafficked; however, the serious

flaws in the Thai government's victim identification procedures

and its aggressive efforts to arrest and deport immigration

violators increased victims' risk of being re-victimised and treated

as criminals. Inadequate victim identification procedures may

have resulted in some victims being treated as law violators

following police raids of brothels. Unidentified victims

were likely among the 190,144 migrant workers subjected

to government citations for lack of proper documentation

during the year, as well as among Rohingya men detained in

sometimes-overcrowded detention facilities.

Prevention

The government continued efforts to prevent trafficking. In

October 2013, Thailand ratified the 2000 UN TIP Protocol.

The government allotted the equivalent of approximately

$6.1 million to conduct anti-trafficking efforts. It conducted

campaigns through the use of radio, television, billboards,

and handouts to raise public awareness of the dangers of

human trafficking throughout the country. Media reported

that the government invested more than the equivalent of

approximately $400,000 in a communication strategy to improve

the public image of its efforts to combat human trafficking.

The use of criminal defamation laws to prosecute individuals

for researching or reporting on human trafficking may have

discouraged efforts to combat trafficking. Four UN special

rapporteurs expressed concerns that an ongoing prosecution

against an anti-trafficking and migrant's rights advocate, in an

act of retaliation for his research documenting alleged trafficking

violations in a food processing factory in Thailand, may have

had the effect of silencing other human rights advocates, and

that the government did not adequately address the underlying

allegations of violations in the report in question. NGOs

expressed similar concerns over a criminal defamation lawsuit

filed by the Thai navy against two journalists in December 2013

for publishing excerpts of media reports that alleged trafficking-related complicity by Thai civilian and navy personnel.

The process to legalise migrant workers involved high fees

and poorly regulated and unlicensed labor brokers, increasing

the vulnerability of migrant workers to trafficking and debt

bondage. The government took no steps to improve this process

or improve laws to regulate inbound recruitment agencies

and fees. The government, through its inaction to process and

approve legal status applications, failed to take measures to

reduce the vulnerability to trafficking of members of Thailand's

hill tribe communities; some of these applications have been

pending for four years. Government labor inspections of 40,963

worksites did not result in the identification of any suspected

cases of labor trafficking. The Marine Police and the Thai navy did not uncover any suspected cases of trafficking during ownership and registration inspections of 10,427 vessels. The government opened seven labor coordination centers, operated by the Ministry of Labor, to increase registration of workers and address labor shortages in the fishing industry and create a centralised hiring hall for prospective workers. More than 10,400 fishermen were registered with 395 employers through the coordination centers. Although it acknowledged the labor shortage was due in large part to some workers' unwillingness to work in the fishing industry due to poor working and living conditions,

the government did not make efforts to significantly improve

these conditions during the year. The government did not pass

revisions to labor laws which could help improve protection for

workers on fishing vessels. Weak law enforcement, inadequate

human and financial resources, and fragmented coordination

among regulatory agencies in the fishing industry contributed to

overall impunity for exploitative labor practices in this sector. In

November 2013, the government passed a ministerial regulation

requiring employers to deduct a refundable fee from workers'

salaries to contribute to a ''repatriation fund''; the imposition of

additional fees and the introduction of additional bureaucratic

requirements on migrant workers could increase their debt

burden. The Ministry of Labor established centers in 10 provinces

to provide information and services to Thai workers seeking

employment overseas, but the Department of Employment

remained ineffective in regulating the excessive fees incurred

by these workers in order to obtain employment, which make

them vulnerable to debt bondage.

During the year, the government revoked the licenses of two labor

recruitment agencies, suspended the license of four agencies,

and filed criminal charges against nine companies (four of

which were fined) and 155 illegal agents that sent Thai workers

abroad. In an effort to prevent child sex tourism, the government

denied entry to 79 known foreign sex offenders and launched

a public awareness campaign warning tourists of the strict

penalties for engaging in sex with minors. The government

also developed a surveillance network on child sex tourism by

training business operators in high-risk areas to identify and

report cases to the police. The government did not make other

efforts to decrease the demand for commercial sex acts or forced

labor. The government did not provide Thai security forces with

anti-trafficking training prior to their deployment abroad on

international peacekeeping missions, though it briefed diplomats

on human trafficking before their departure to overseas posts.

Sounds like the General might be the best defence witness in a certain action against some journalists.

Would not be surprised if some common sense soon results in the strike of a pen!

The benefit to the military would be immeasurable.

Posted by Manowar on June 20, 2014 23:07