PHUKET: When we were ushered into the Restricted Area inside the Immigration Centre, we didn't know what to expect.

Packed tight behind the padlocked grille leading to the stairs were the Rohingya. There were about 60 of them, squatting.

In riot scenes at prisons, angry inmates are usually yelling and chanting and banging the bars.

The Rohingya are not like that. Their heads were all down. There was a soft, collective murmur. They were praying.

Certainly, there must have been some disobedience and perhaps even a small amount of violence for the 261 men being held at Phang Nga Immigration Centre to break from their cells upstairs.

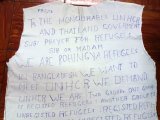

Our task now was to try to end their protest. For six months, these men, along with about 1700 others, have been kept as detainees in Thailand.

The Thai Government was supposed to announce at the end of the half-year, a deadline they set themselves, what the status and the future would be for these luckless women, children and men.

But there appears to have been a breakdown in communications. The government's own deadline passed two weeks ago.

The Rohingya? They are still prisoners in Thailand.

We've met Rohingya before, on boats off Phuket, behind bars or limping from a hospital in the border port of Ranong to jail, suffering from wounds said to be inflicted by the Burmese military.

They're stateless and unwanted in their home country, and the only reason they come to Thailand is to pass through on the way to what they envisage is a better life in Malaysia.

The crisis that developed into a four-hour face-off yesterday north of Phuket appears to have been yet another breakdown in communications.

The Immigration officers, effectively prison wardens, do not speak Bengali, the Rohingya language, and the Rohingya do not speak Thai.

How do the reluctant jailers and their prisoners manage on a day-to-day basis, we wondered.

Now, in desperation, we were being asked to help deliver an ultimatum, across the language barrier and the entrance grille.

Using her iPhone, my colleague Chutima Sidasathian managed to contact a translator we've used on previous Rohingya stories. An immigration official held the loudspeaker. There was, suddenly, a loud voice.

Once the Rohingya heard the Bengali language boom, they lifted their heads. We could see their faces for the first time. Young, thin faces.

Somehow, the message got across. About 3pm, the doors would be open. Those Rohingya who wanted to move out could leave for cells at police stations around the province.

When told he had the choice of going back up the stairs or into a police truck, one Rohingya teenager told our translator: ''We don't want to go back up. Shoot us dead here or throw us back into the sea to die. It's the end for us.''

Before we arrived, the Immigration officers and police had tried to use a high-pressure hose from a water tanker to clear the stairway.

We weren't there, but the water pressure may not have been too great. The Rohingya were not budging.

Over the next hour or so, police arrived in greater numbers, brought in from surrounding provinces to deal with the emergency.

Some of them were fitted out with riot shields, helmets and batons. Several hundred of them then packed into the area around the Immigration centre building.

We were ordered out of the compound, for the second time. Somehow, we finished up back inside, to look on from a distance.

One by one, in single file, the Rohingya made their way through the walls of police, and into the waiting police trucks.

The Rohingya, one has to hope, will never have another day to end Ramadan quite like like this one.

Despite the lack of communication, the whole process was handled with discipline and skill.

Yet how much easier it would have been, though, if the Rohingya and the police could have talked to each other.

As the four-hour face-off came to an end, we were left to ponder how the Thai government could not have thought to provide translators.

About then, the Bengali speaking woman we had called to help arrived after a long ride on her motorcycle. The Immigration officials declined to pay. Phuketwan footed the bill.

And so ended a day of deep anxiety for Thailand's innocent prisoners and their jailers.

We can only hope that one day soon, the prayers of the Rohingya - and probably those of their reluctant keepers - are answered.

Packed tight behind the padlocked grille leading to the stairs were the Rohingya. There were about 60 of them, squatting.

In riot scenes at prisons, angry inmates are usually yelling and chanting and banging the bars.

The Rohingya are not like that. Their heads were all down. There was a soft, collective murmur. They were praying.

Certainly, there must have been some disobedience and perhaps even a small amount of violence for the 261 men being held at Phang Nga Immigration Centre to break from their cells upstairs.

Our task now was to try to end their protest. For six months, these men, along with about 1700 others, have been kept as detainees in Thailand.

The Thai Government was supposed to announce at the end of the half-year, a deadline they set themselves, what the status and the future would be for these luckless women, children and men.

But there appears to have been a breakdown in communications. The government's own deadline passed two weeks ago.

The Rohingya? They are still prisoners in Thailand.

We've met Rohingya before, on boats off Phuket, behind bars or limping from a hospital in the border port of Ranong to jail, suffering from wounds said to be inflicted by the Burmese military.

They're stateless and unwanted in their home country, and the only reason they come to Thailand is to pass through on the way to what they envisage is a better life in Malaysia.

The crisis that developed into a four-hour face-off yesterday north of Phuket appears to have been yet another breakdown in communications.

The Immigration officers, effectively prison wardens, do not speak Bengali, the Rohingya language, and the Rohingya do not speak Thai.

How do the reluctant jailers and their prisoners manage on a day-to-day basis, we wondered.

Now, in desperation, we were being asked to help deliver an ultimatum, across the language barrier and the entrance grille.

Using her iPhone, my colleague Chutima Sidasathian managed to contact a translator we've used on previous Rohingya stories. An immigration official held the loudspeaker. There was, suddenly, a loud voice.

Once the Rohingya heard the Bengali language boom, they lifted their heads. We could see their faces for the first time. Young, thin faces.

Somehow, the message got across. About 3pm, the doors would be open. Those Rohingya who wanted to move out could leave for cells at police stations around the province.

When told he had the choice of going back up the stairs or into a police truck, one Rohingya teenager told our translator: ''We don't want to go back up. Shoot us dead here or throw us back into the sea to die. It's the end for us.''

Before we arrived, the Immigration officers and police had tried to use a high-pressure hose from a water tanker to clear the stairway.

We weren't there, but the water pressure may not have been too great. The Rohingya were not budging.

Over the next hour or so, police arrived in greater numbers, brought in from surrounding provinces to deal with the emergency.

Some of them were fitted out with riot shields, helmets and batons. Several hundred of them then packed into the area around the Immigration centre building.

We were ordered out of the compound, for the second time. Somehow, we finished up back inside, to look on from a distance.

One by one, in single file, the Rohingya made their way through the walls of police, and into the waiting police trucks.

The Rohingya, one has to hope, will never have another day to end Ramadan quite like like this one.

Despite the lack of communication, the whole process was handled with discipline and skill.

Yet how much easier it would have been, though, if the Rohingya and the police could have talked to each other.

As the four-hour face-off came to an end, we were left to ponder how the Thai government could not have thought to provide translators.

About then, the Bengali speaking woman we had called to help arrived after a long ride on her motorcycle. The Immigration officials declined to pay. Phuketwan footed the bill.

And so ended a day of deep anxiety for Thailand's innocent prisoners and their jailers.

We can only hope that one day soon, the prayers of the Rohingya - and probably those of their reluctant keepers - are answered.