PHUKET: Eight months after deadly communal clashes broke out in Burma's Rakhine state, tens of thousands of people are still unable to access urgently needed medical care, the international medical humanitarian organisation Doctors Without Borders/Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) says.

MSF calls on government authorities and community leaders to ensure that all people of Rakhine can live without fear of violence, abuse and harassment, and that humanitarian organisations can assist those most in need.

''It is among people living in makeshift camps in rice fields or other crowded strips of land that MSF is seeing the most acute medical needs,'' said Arjan Hehenkamp, MSF general director.

''Ongoing insecurity and repeated threats and intimidation by a small but vocal group within the Rakhine community have severely impacted on our ability to deliver lifesaving medical care.''

In June 2012, deadly communal clashes led authorities to place Burma's Rakhine State under an official state of emergency.

An estimated 75,000 people were displaced and many homes were burned down. Further outbreaks of violence in October exacerbated the humanitarian crisis, forcing about 36,000 more people out of their homes and into makeshift camps, which do not have sufficient shelter, water, sanitation, food or health care.

Many people who are still in their homes have also been affected by a lack of access to medical care due to the violence.

Camp residents have many critical medical needs. Skin infections, worms, chronic coughing and diarrhea are the most common ailments that MSF teams have encountered in more than 10,000 medical consultations in the camps since October.

Malnutrition rates vary, but MSF has found alarming numbers of severe acutely malnourished children in several camps. Although clean water is often available in sufficient quantities, some of the displaced are denied access to it. Pregnant women are also denied access to medical care.

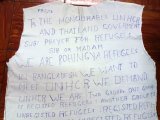

While the needs remain acute, MSF medical teams face continued threats and hostility. In pamphlets, letters, and Facebook postings, MSF and others have been repeatedly accused of having a pro-Rohingya bias by some members of the Rakhine community.

It is this intimidation, and not formal permission for access, that constitutes the primary challenge facing MSF. The authorities, however, can do more to make it clear that violent threats against health workers is unacceptable.

''Our repeated explanations that MSF only seeks to provide medical aid to those who need it most is not enough to forestall the accusations,'' Hehenkamp said.

'MSF urges supportive community leaders and government authorities to do more to counteract the threats and intimidation so that humanitarian aid can be delivered to those who urgently need it.''

MSF has been providing health care throughout the world, including in Burma, for decades, meeting the medical needs of millions of people, regardless of ethnic origin.

Across Burma, MSF provides more than 26,000 people with lifesaving anti-retroviral treatment for AIDS and was among the first responders to cyclones Nargis and Giri, providing medical assistance, survival items and clean water to tens of thousands of people.

MSF has worked for the past 20 years in Rakhine State, providing primary and reproductive health care as well as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis treatment.

Prior to June, MSF conducted approximately 500,000 medical consultations per year. Since 2005, MSF has treated more than 1.2 million people from all ethnic groups in Rakhine State for malaria.

MSF calls on government authorities and community leaders to ensure that all people of Rakhine can live without fear of violence, abuse and harassment, and that humanitarian organisations can assist those most in need.

''It is among people living in makeshift camps in rice fields or other crowded strips of land that MSF is seeing the most acute medical needs,'' said Arjan Hehenkamp, MSF general director.

''Ongoing insecurity and repeated threats and intimidation by a small but vocal group within the Rakhine community have severely impacted on our ability to deliver lifesaving medical care.''

In June 2012, deadly communal clashes led authorities to place Burma's Rakhine State under an official state of emergency.

An estimated 75,000 people were displaced and many homes were burned down. Further outbreaks of violence in October exacerbated the humanitarian crisis, forcing about 36,000 more people out of their homes and into makeshift camps, which do not have sufficient shelter, water, sanitation, food or health care.

Many people who are still in their homes have also been affected by a lack of access to medical care due to the violence.

Camp residents have many critical medical needs. Skin infections, worms, chronic coughing and diarrhea are the most common ailments that MSF teams have encountered in more than 10,000 medical consultations in the camps since October.

Malnutrition rates vary, but MSF has found alarming numbers of severe acutely malnourished children in several camps. Although clean water is often available in sufficient quantities, some of the displaced are denied access to it. Pregnant women are also denied access to medical care.

While the needs remain acute, MSF medical teams face continued threats and hostility. In pamphlets, letters, and Facebook postings, MSF and others have been repeatedly accused of having a pro-Rohingya bias by some members of the Rakhine community.

It is this intimidation, and not formal permission for access, that constitutes the primary challenge facing MSF. The authorities, however, can do more to make it clear that violent threats against health workers is unacceptable.

''Our repeated explanations that MSF only seeks to provide medical aid to those who need it most is not enough to forestall the accusations,'' Hehenkamp said.

'MSF urges supportive community leaders and government authorities to do more to counteract the threats and intimidation so that humanitarian aid can be delivered to those who urgently need it.''

MSF has been providing health care throughout the world, including in Burma, for decades, meeting the medical needs of millions of people, regardless of ethnic origin.

Across Burma, MSF provides more than 26,000 people with lifesaving anti-retroviral treatment for AIDS and was among the first responders to cyclones Nargis and Giri, providing medical assistance, survival items and clean water to tens of thousands of people.

MSF has worked for the past 20 years in Rakhine State, providing primary and reproductive health care as well as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis treatment.

Prior to June, MSF conducted approximately 500,000 medical consultations per year. Since 2005, MSF has treated more than 1.2 million people from all ethnic groups in Rakhine State for malaria.